Premature optimisation is a trap you can easily fall into whenever you are making or designing something. In some ways, it feels wrong to do something badly when you know you could do it better with a little more time. However, it is almost always best to get something working (even if it’s not perfect) rather than striving for an elegant solution that doesn’t yet work. You can always implement the faster, more accurate, or more elegant method later—and often you don’t need to. It is also far easier to improve something that already works than to build something from scratch.

Over the last few days, I have been working on a project that involves decoding a high-frequency, frequency-modulated (FM) audio signal. I recorded this signal on my phone, which has stereo microphones, and spent some time writing a clever beam-forming algorithm that adjusts the amplitude and phase of the signals received by the two microphones to increase the FM signal strength while rejecting background noise. The algorithm used simulated annealing to optimise the amplitude and phase adjustments, and it worked very well in a set of simulated examples that I used for testing.

However, it did not work well on the actual data I collected. I spent quite a while fixing and tuning parameters but could not get it to perform properly. Eventually, I did what I should have done from the beginning: I conducted a real experiment and carried out some simple data analysis to understand what was happening.

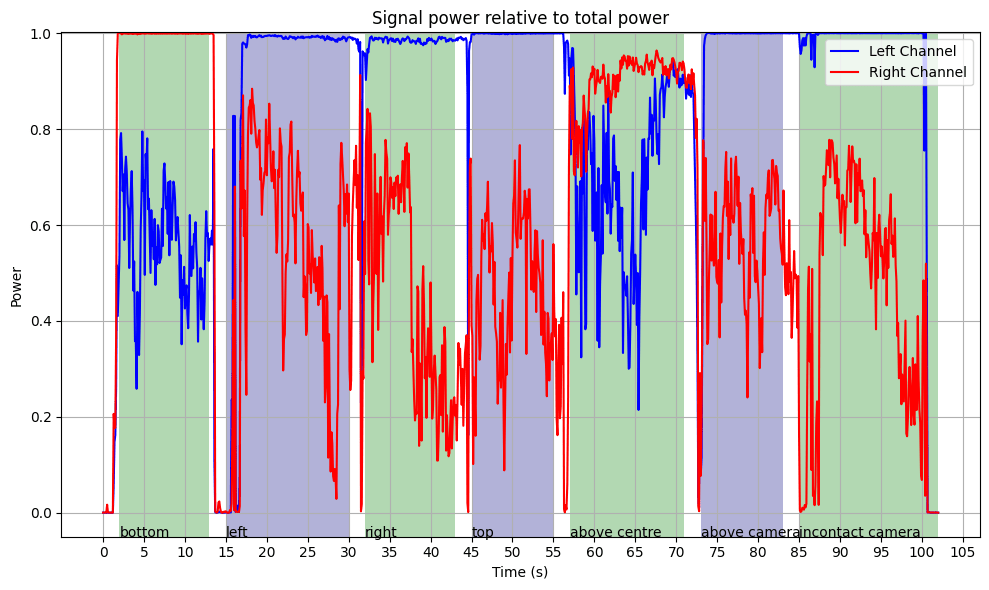

I moved the source around different parts of my phone and plotted the power in the FM carrier band. After looking at the plot, it became immediately obvious why the beam-forming algorithm never worked: the sound was far too directional. (This makes complete sense, given that it was a high-frequency sound.) There was never a point where the sound was picked up strongly by both microphones; it was only ever picked up by one at a time. I should have used a much simpler approach: just take the output from whichever channel had the highest power in the carrier band—a single line of code—rather than hundreds.

In fact, the plot of the ratio of signal power to total power implies that in this example, the signal typically makes up the vast majority of the received power. However, the carrier band power is only a proxy for the actual signal, since it also includes FM-encoded noise that is not truly signal. Therefore, the true ratio of signal power to total power is somewhat lower.