Abstract

This project explores a method to extract and decode high-quality ECG data from the KardiaMobile device without relying on proprietary APIs. By leveraging the original device’s frequency-modulated (FM) audio output, I developed a pipeline for demodulating, calibrating, and denoising the signal using quadrature demodulation and adaptive filtering techniques. The approach successfully removes noise, including mains hum and harmonics, and reconstructs the ECG signal with high fidelity. This method successfully produced high-quality ECG signals, clearly showing key features such as the P-waves, the QRS-complex, and T-waves. This accessible and cost-effective solution enables incidental ECG data collection for research purposes, using the KardiaMobile’s affordable hardware.

Introduction

I’ve been interested in electrocardiograms (ECG or EKG) for several years. Back in 2017, I attempted to build my own ECG machine. While the project didn’t progress very far (resulting in a few damaged operational amplifiers), it sparked a lasting fascination with ECG technology.

This interest resurfaced when I discovered the KardiaMobile ECG devices. These pocket-sized, battery-powered machines connect to a smartphone and enable basic ECG recordings. They are approved by both the British National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The KardiaMobile 6L even records three channels, allowing for six-lead ECGs to be synthesized. This elegant, pre-packaged solution immediately reminded me of my earlier ECG project—only someone else had done all the hard work.

The KardiaMobile is a compact device, approximately 80 mm long and 30 mm wide, with two metal electrodes for recording ECGs. It outputs the ECG signal which is then picked up by the smartphone app that seems to work on almost any phone with recordings limited to 5 minutes by the Kardia app. To record an ECG you start up the app and set it to record an ECG then place your left index finger on the left electrode and your right index finger on the right electrode. The app then detects that an ECG is now being generated and starts recording it, plotting it live on the screen. After the ECG has been acquired you can then save the ECG in the app along with tags and notes and you can also generate PDF reports that plot the ECG on a page along with basic information.

The app can even detect a few heart conditions – although it’s no substitute for a cardiologist.

While KardiaMobile devices work seamlessly with the official Kardia app to generate ECG plots and reports, my interest lay elsewhere: I wanted access to the raw ECG data to create custom visualizations and analyses. My goal wasn’t related to health monitoring or diagnosis; I simply wanted to explore the data and create neat charts.

The Problem: How to access the data?

The KardiaMobile 6L transmits ECG data to a smartphone via Bluetooth, a secure two-way protocol with encryption and numerous parameters. Extracting raw data directly seemed like a dead end. I briefly considered tracing ECG plots from the app’s reports, but having tried similar methods before, I knew how error-prone they could be. Kardia does offer an API, but it appears to be intended for clinical use, not individual hobbyists—they never responded to my inquiries.

Chance solution: The older version uses sound waves to transmit the data

By chance, I watched a cardiologist’s review of the KardiaMobile on YouTube. He mentioned that the device uses sound waves to communicate with the app. While this seemed preposterous, I decided to investigate. To my surprise, I discovered that the original KardiaMobile (single-lead) indeed transmits its signal using a frequency-modulated (FM) sound wave in the 18–20 kHz range, as specified in its documentation. The key details include:

- A carrier frequency of 19 kHz

- Frequency modulation with a scale of 200 Hz/mV

- A 10 mV peak-to-peak range

- A frequency response from 0.1 Hz to 40 Hz

Armed with this information, I mocked up a test: I generated a synthetic heartbeat, frequency-modulated it, and played it through my computer. To my amazement, the Kardia app detected it as a healthy heartbeat with a BPM of 75—precisely what I had set. Confident in my understanding of the encoding process, I purchased a KardiaMobile device to explore further.

I actually found out all of this information before purchasing an ECG machine. So I mocked up an example heartbeat, frequency modulated it and played it on my computer. The Kardia app detected it as a healthy heartbeat with a BPM of 75, exactly what I had set it as. At this point, I was pretty sure that I understood the encoding process since I had effectively reverse-engineered the protocol and had a successful test on the Kardia app. The output is one-way, analogue, and not encrypted. With this newfound confidence in my plan, I bought a KardiaMobile ECG.

Optimising the signal acquisition

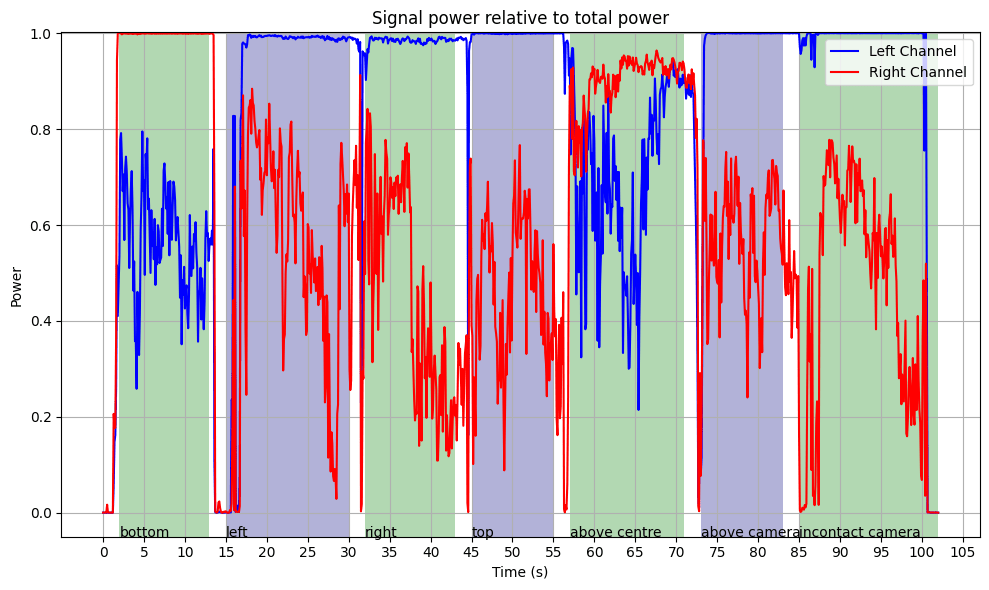

While initially concerned about microphone selection, I found that the microphones on my Samsung Galaxy S20 Ultra worked well—FM modulation is forgiving. I also experimented with beamforming algorithms to improve signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), but they failed due to the directional nature of the high-frequency signal. A simpler method, selecting the channel with the most power in the carrier band, proved effective. This shouldn’t have been surprising as the app also works by using the built-in microphone on my phone, however initially I wasn’t sure how much signal processing they were doing so I wanted to get the best initial signal.

After I did a quick experiment where I held the Kardiamobile near my phone in different places I was able to work out where the best place to hold it was. I ended up using the bottom of the phone for all of my tests as it yielded high signal and was convenient.

Decoding the ECG Signal

The decoding process follows these steps:

- Input and Preprocessing:

- Read the audio file and determine its sample rate.

- If the signal has multiple channels, select the one with the highest power in the carrier band.

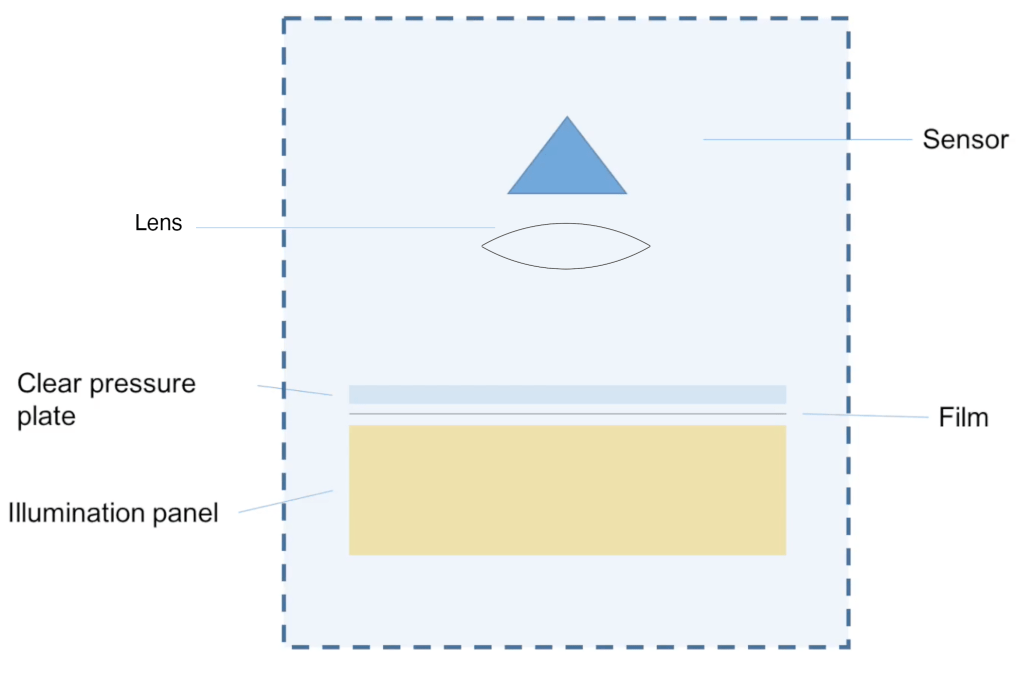

- FM Demodulation:

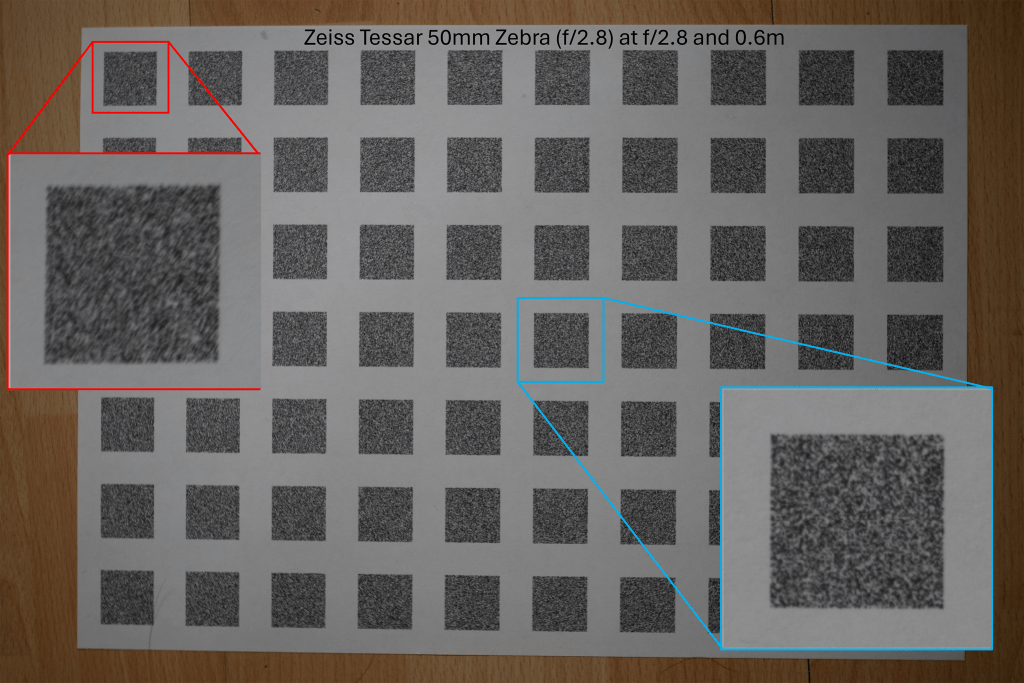

- I tested several demodulation methods, with quadrature demodulation yielding acceptable results with a simple algorithm. This calculates the frequency deviation from the carrier frequency.

- Calibration and Downsampling:

- Convert the frequency deviations to voltage using the scale of 200 Hz/mV.

- Downsample the signal to 600 samples/second, as the 19 kHz carrier signal has been removed so high temporal resolution isn’t needed.

- Denoising and Filtering:

- Identify and filter out mains hum (e.g., 50 Hz in the UK, including harmonics). I implemented an adaptive Fourier-based filter to detect and remove the specific mains frequency and its harmonics.

- Remove low-frequency noise (<0.52 Hz) and high-frequency noise (>40 Hz) using a zero-phase filter to avoid adding in phase distortion to the signal.

- Post-Processing:

- Apply wavelet denoising using DB4 wavelets to remove noise without reducing the sharp features in the signal.

- Trim extraneous noise at the start and end of the recording.

Removing mains hum

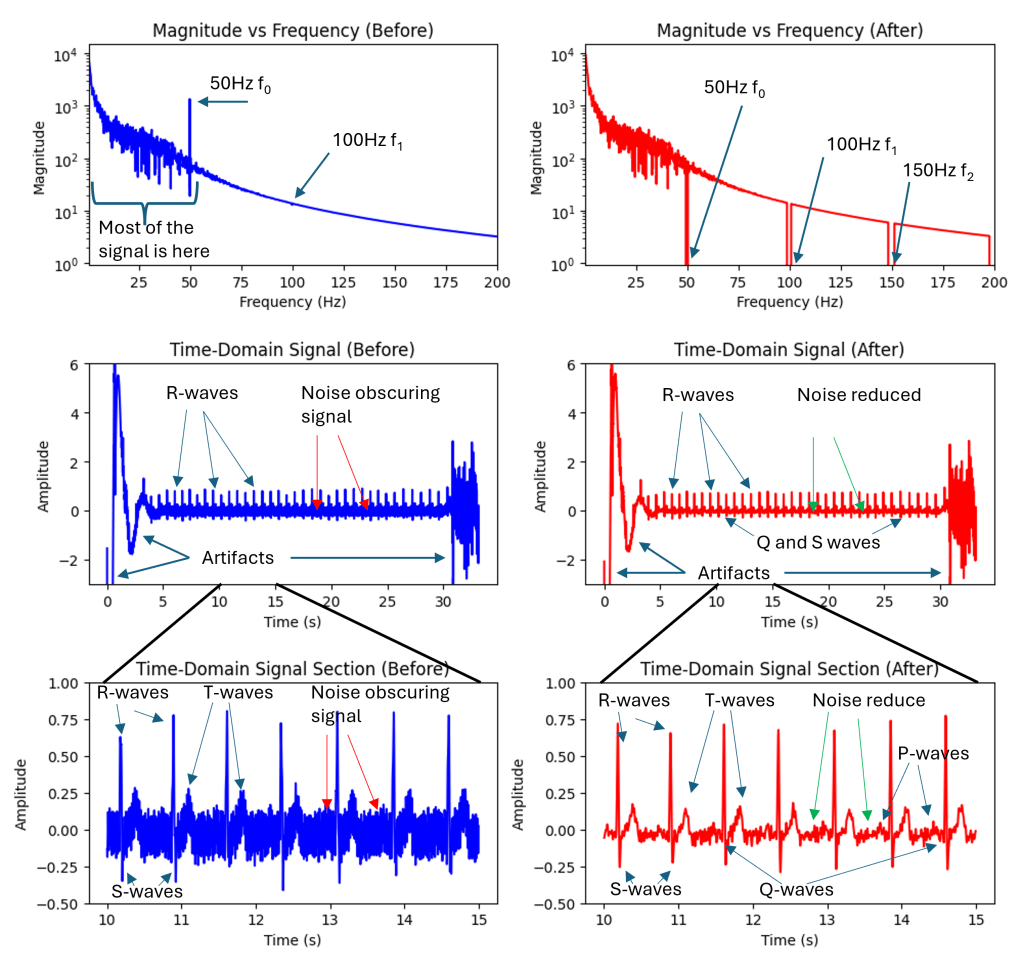

The main source of noise was mains hum picked up by the Kardia ECG itself. An example of the filtering process is shown below, where the sharp peak near 50 Hz. I used an adaptive filtering approach that ensures precise removal even when the mains frequency slightly deviates (e.g., 49.92 Hz instead of 50 Hz) removing the minimum additional signal.

Detected Mains Frequency: 49.92 Hz

Filtering 49.92 Hz: Range [49.42, 50.42]

Filtering 99.84 Hz: Range [98.85, 100.84]

Filtering 149.77 Hz: Range [148.27, 151.26]

Filtering 199.69 Hz: Range [197.69, 201.69]

Filtering 249.61 Hz: Range [247.11, 252.11]

Since the mains frequency component is so strong the filtering process also needs to be very strong. A second-order filter with a cut-off frequency of 40Hz still left a large amount of 50Hz noise in the signal. Interestingly this 50Hz hum is not hum picked up by the microphone it’s actually hum picked up inside the Kardia unit. I used second-order zero-phase filters that avoid adding phase artifacts to the signal. Traditional filters like Butterworth filters add a phase shift that varies by frequency which can be particularly harmful to these kinds of signals.

Following this additional denoising was applied using wavelet transforms and Daubechies 4 (DB4) wavelets. This transforms the time domain signal into a signal that is made up of short bursts of short packets of waves. These efficiently model bursty signals like heartbeats and poorly model totally random signals like noise. In the wavelet domain, you can filter out small wavelet coefficients that are more likely to correspond to noise and keep coefficients of greater magnitude that are more likely to correspond to my heartbeat signal.

I then added some basic signal processing was used to estimate where the real signal started and finished (i.e., to remove the initial and final bits of noise from when Kardia unit was off).

Results

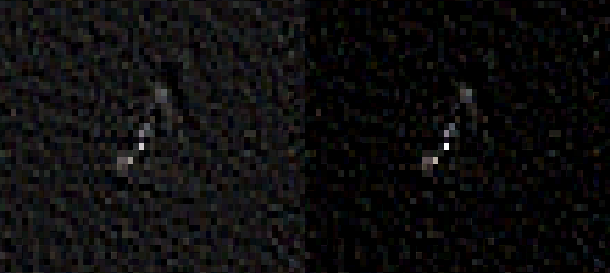

After all of these steps, I was able to produce high-quality ECG results that can be exported in any output format (.csv, .xls, .npy, .mat etc) and plotted in any way desired. Kardia likely adds lots of useful signal processing that I’m not able to reproduce at this time however I was able to produce ECG results that clearly show the main features of the expected heartbeat signal including R-waves, T-waves, S-waves, and the QRS complex.

Conclusion

The result of all this is a high-quality method of recording and exporting ECG data from the Kardiamobile device without using their API which is not available to the general public. Since the Kardia device is very inexpensive – I paid around £50 (60USD or 60EURO) for mine – and this method is easy to reproduce this may open up new avenues for incidental ECG usage in a research setting. This may enable researchers to extract ECG signals from inexpensive hardware, facilitating incidental ECG usage in various research settings.

This method is obviously not appropriate for monitoring or diagnosing any kind of health condition.

An extremely rough version of this code is available at my github: https://github.com/joshuamcateer/kardiadecode